You Can’t Live in the Lab

By: Douglas G. Ciocca

Attribution is reflexive in managing money. Understanding why things happen in markets is critical for a variety of reasons: 1) It’s formative philosophically; 2) It helps to avoid future mistakes and; 3) It triggers tactical transitions.

Often, as the saying goes, knowledge is power. Thank you, Sir Francis Bacon.

As a portfolio manager, you become conditioned, and almost look forward to, dissecting the myriad sources of volatility and price dislocation. I almost feel like a research doc (with far less schooling) in the deconstruction of the market’s DNA. It is commonly the source of sleepless nights, challenged convention and refortification of models.

However, this most recent spate of capital market consternation has proven far less challenging in the discovery of its catalyst. In fact, it is so easy to unearth, it’s essence is an abbreviation….it’s the Fed!

The Fed, also known as the Federal Reserve Bank, is charged with setting the course of domestic monetary policy. This is accomplished chiefly through modifying the cost of capital by employing mechanisms to influence interest rates.

Led by a gentleman named Jerome “Jay” Powell, this band of apolitical banking authorities (and some 400 behind-the-scenes PhD’s) attempts to soften the peaks and valleys of the business cycle by adhering to a Congressionally defined dual mandate of price stability and full employment.

The Fed always has the market’s ear. The Fed’s Open Market Committee meets 8 times per year and shares insights and anecdotes attendant to any policy action that emanates and the market hangs on every word. Former Fed Head Alan Greenspan was fittingly known as, “the Maestro.”

The Fed’s bearing on current market moves is a function of its policy being simultaneously 1) pent-up and 2) punitive.

Pent-up.

A little more than 3 years ago, in the medical depths of the pandemic, the Fed unleashed a torrent of liquidity into the financial system by cutting rates to zero. Literally zero. The goal was to eliminate impediments to borrowing funds in order to avoid the maximum adverse outcomes of a halted economy. In many respects, it worked.

Buttressed by an equally accommodative fiscal policy, global economic activity bent but didn’t break as the bridges to vaccinations and semi-normal existences were constructed.

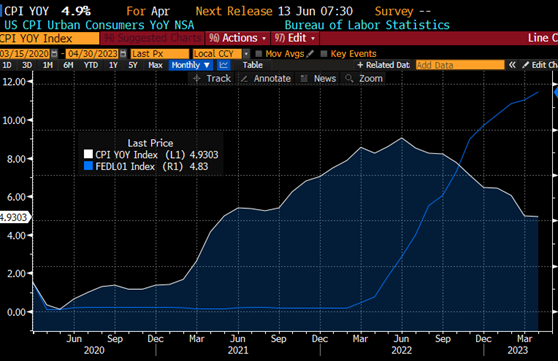

The consequence of that action was revealed in the high rates of inflation that followed. CPI (Consumer Price Index that measures the overall change in consumer prices based on a representative basket of goods and services over time) had fallen to 0.12% in May of 2020, only to pivot and climb, virtually without disruption, to its peak of 9.10% in June of 2022.

It was during this parabolic ascendency that the Fed insisted on categorizing inflation as, “transitory”1 and resisted raising interest rates until March of 2022 (nearly a full 2 years off the low print in CPI!) By that time, this cost-of-living measure hit a 7.9% year-over-year increase. Not quite what you would consider proactive or prescient. Just pent-up.

Interestingly, their initiation of rate rises transpired 3 weeks after the launch of an enduring military offensive by Russia into Ukraine. This conflict disrupted the global flow of energy and agricultural commodities, creating upward pricing pressure from the supply side and foiled the Fed from extracting price declines on products whose availability became inhibited. Hmmmm….if only they had started sooner…..

Punitive.

Flash-forward 14 months from the initial rate hike and they are still at it! The Fed has raised rates at each of the last 10 meetings (unprecedented) for a total lift in the Fed Funds Rate to 5.25%. The speed of such a reversal is also unprecedented. And while we’re setting records, throw in the incidence of 4 consecutive meetings when they raised rates by ¾ of 1%. If haste makes waste, then their urgency in implementation can certainly explain 2022’s cross asset class correlation of poor performances.

Correspondingly, inflation has been in a steady and considerable decline. After peaking at 9.1% in June, last week’s latest CPI reading came in at 4.9%.

A casual observer would consider this trend to be pleasing to the pliers of policy, but they would be sorely mistaken. In direct contrast to one of the Fed communique’s most common cliches: “the effects of monetary policy are long and variable2,” they are exhibiting little interest in relenting.

As recently as yesterday morning, the President of the Minnesota Fed, Neel Kashkari, stated: “THE FED HAS LONG WAY TO GO TO GET INFLATION TO 2% GOAL3.” And on Friday, the President of the Richmond Fed, Tom Barkin relayed that he was, “`VERY OPEN’ TO MORE RATE HIKES3.”

This illuminates a stunning paradox of patience and brings into consideration an old Wall Street adage: “The Fed goes until they break something.”

The Paradox of Patience.

As a part of their dual-mandate that concerns price stability, the Fed historically targets 2% as the “sweet spot for inflation – low enough for consumer comfort but relaxed enough for the economy to flourish, according to Fed doctrine settled years ago.” 4

And yet, the Fed let CPI run up to 7.9% before tightening policy in 2022, indicating an interest in letting the economy run hot before being addressed. Said better in an NPR article from August of 2020:

“The punch bowl can stay.

The Federal Reserve is adjusting its long-term policy on inflation and employment, and says it will no longer tap the brakes preemptively to prevent the economy from overheating — a job famously likened to taking away the punch bowl just as the party gets going.

For decades after the price hikes of the 1970s, the central bank was on high alert for inflation, raising interest rates whenever unemployment fell “too low,” on the theory that would spark runaway prices.

But in recent years, the Fed has been more concerned with prices that aren’t rising fast enough. Inflation has remained stubbornly below the Fed’s 2% target, even when unemployment was at half-century lows.

Under the new policy, which was approved unanimously by the central bank’s rate-setting committee, the Fed will not concern itself with an employment picture that is too strong, only a job market that is too weak. And after a long period of inflation that’s too low, the Fed will tolerate a period of higher prices, in order to achieve an average inflation rate of 2%.”

You don’t need a special decoder ring to identify the asymmetry of this principle. Applied in any ordinary period in economic history, it would lead to metaphorical overindulgence and be followed by metaphorical starvation- an undesirable sequencing for sustainability.

But the period during which this new experiment has been undertaken is like no prior period in economic history, courtesy of a pandemic that triggered record-setting fiscal and monetary stimulus followed by a regional war in one of the most important commodity-exporting corners of the world.

The Fed, and all 400 of their PhD’s, seem to have misunderstood the environment in which they attempted to perform a controlled experiment, as this can only be effective when an independent variable can be precisely manipulated. In a dynamic system, like the financial markets, all inputs (or states) are dependent variables, rendering their undertaking as, at best, highly fallible, and at worst, potentially destructive.

“The Fed goes until they break something.”

Without going into the deep details of the recent regional banking crisis, suffice it to say that the speed and longevity of the Fed rate hikes could be partially responsible.

Banks had been holding record levels of deposits as their customers were flush coming out of the pandemic and risk was being underwritten by a near-zero interest rate environment conducive to capital raising.

Those customer deposits were invested in accordance with Fed-instituted guidelines, adhering to new standards implemented after the global financial crisis. No sub-prime mortgage pools or synthetic CDO’s, solely in high-quality, mostly government debt obligations.

The banks didn’t take credit risk, they took duration risk. Essentially, they invested in high-grade bonds with average maturities exceeding what could be necessary to satisfy customer withdraw requests.

A wise man once asked me, “do you get mad at the rain if you forget your umbrella?” This accountability parable reinforces the responsibility of the individual, or banker in this case, to prepare to fail (or get wet!) if they fail to prepare.

Perhaps, a little grace could be granted the banker if the weatherman, in this case Jay Powell, claimed convincingly that rain was nowhere near the radar! For example, when he famously said in the summer of 2020 that he was, “not even thinking about thinking about raising rates6,” or in 2021, when he claimed that the tightening process may not convene until the end of 2023…..7

Does this banking debacle constitute a breakage in the system? Are there enough backstops in place to prevent it from being systemic? Should the banks have been better at managing interest rate risks and customers better at diversifying deposits? Answers to all these questions will be told by time, but one thing we cynically know for sure: the Fed is really good at preventing the LAST crisis, just not so strong in being progressive.

The Fed and the markets sit today at an interesting inflection point and we are hopeful that the characteristic the Fed claims at every meeting will begin to be incorporated …..that of being “data dependent.”

What’s done is done. Also, what’s done has undeniably contributed to the destabilization in bond and stock markets in 2022, in the banking business in 2023 and in the direction of the global economy into the near future.

In my opinion, the Fed has made 2 significant policy errors which have intensified market dislocation and economic uncertainty and that have real consequences.

The first error was waiting too long to begin extracting liquidity from the economy. With a CPI level of 7.9%, characterized as “transitory,” their deliberation and inaction served as fuel to the fire of inflation.

The second error was adjusting interest rates too quickly once they started. “Long and variable lags,” connotes the need for patience with the incubation period from implementation-to-impact. Yet they aren’t exhibiting any, and their inter-meeting rhetoric betrays the progress that’s been made when they refer to inflation solely as “sticky.” 9.1% to 4.9% in 9 months seems reasonably smooth to me, especially with the 3 & 6 month run-rates coming in below 3.5%. Please chill out.

Lastly, they run the risk of a third policy mistake: going too far with rate hikes. While the investing world has put the Fed on a pedestal, (which many of their media mongering members seek to stoke), they have limitations with their authority.

The Fed is trying to fix a societal, fiscal and monetary problem with a limited set of tools. The consequences to an overreach are considerable. They need to acknowledge that they cannot and should not live in the lab. They need to assess and not guess. They need to admit that they are dealing daily with unknowns and that the inconsistencies in their talk vs. their action send strange signals to the markets.

2 policy errors are plenty. Take a breath and let the impact of your actions percolate prior to proceeding. Please.

2 https://twitter.com/NickTimiraos/status/1552365486926663690

3 Source: Bloomberg Market Data

5 https://www.npr.org/2020/08/27/906661421/fed-prepared-to-let-economy-run-hotter

6 https://twitter.com/NickTimiraos/status/1270790117641392128

The views expressed herein are those of Doug Ciocca on May 16th, 2023 and are subject to change at any time based on market or other conditions, as are statements of financial market trends, which are based on current market conditions. This market commentary is a publication of Kavar Capital Partners (KCP) and is provided as a service to clients and friends of KCP solely for their own use and information. The information provided is for general informational purposes only and should not be considered an individualized recommendation of any particular security, strategy or investment product, and should not be construed as investment, legal or tax advice. Different types of investments involve varying degrees of risk, and there can be no assurance that any specific investment or strategy will be suitable or profitable for a client’s investment portfolio. All investment strategies have the potential for profit or loss and past performance does not ensure future results. Asset allocation and diversification do not ensure or guarantee better performance and cannot eliminate the risk of investment losses. The charts and graphs presented do not represent the performance of KCP or any of its advisory clients. Historical performance results for investment indexes and/or categories, generally do not reflect the deduction of transaction and/or custodial charges or the deduction of an investment management fee, the incurrence of which would have the effect of decreasing historical performance results. There can be no assurances that a client’s portfolio will match or outperform any particular benchmark. KCP makes no warranties with regard to the information or results obtained by its use and disclaims any liability arising out of your use of, or reliance on, the information. The information is subject to change and, although based on information that KCP considers reliable, it is not guaranteed as to accuracy or completeness. This information may become outdated and KCP is not obligated to update any information or opinions contained herein. Articles herein may not necessarily reflect the investment position or the strategies of KCP. KCP is registered as an investment adviser and only transacts business in states where it is properly registered or is excluded or exempted from registration requirements. Registration as an investment adviser does not constitute an endorsement of the firm by securities regulators nor does it indicate that the adviser has attained a particular level of skill or ability.